PAPER READ ON “POETRY AND TIME”

AT THE SYMPOSIUM OF STRUGA POETRY FESTIVAL, YUGOSLAVIA

23rd August 1984

Poetry has been defined by poets, critics and other students of culture in various ways and in various contexts. It is therefore appropriate to limit our discussion very briefly to the broadest concepts of poetry found in the West and the East. Ezra Pound, one of the foremost poets and critics refer to poetry in the following words, “On closer analysis, I find that I mean something like maximum efficiency of expression; I mean that the writer has expressed something interest in such a way that one cannot re-say it more effectively. I also mean something associated with discovery. The artist must have discovered something – either of life itself or of the means of expression.” (Literary Essays of Ezra Pound, Ed T. S. Eliot.)

The enormous literature in and on poetry and the scholarly criticism coming down orally and in writing from the time of Bharata Muni in India up to-date shows how the oriental poet is attempting to capture the nations poetic imagination. Ananda Coomaraswamy, the renowned art critic is the best authority that we can quote to discern a brief introduction to this poetry.

“We approach the essential problem; what is art? What are the values of art from an Asiatic point of view? A clear and adequate definition can be found in Indian works on rhetoric. According to the Sathiya Darpana 1.3, Vakyam Rasatmakam Kavyam”, art is a statement infirmed by ideal beauty. Statement is the body, Rasa, the soul of the work; the statement and the beauty cannot be decided as separate identities. (Coomaraswamy – selected Papers 1 Ed. Roger Lipsey)

We now come to the next stage of our inquiry – the concept of time. Aristotle defines time as the number of motions relative to before and after. In modern philosophy the men who have most concerned themselves with time are Leigniz and Kant. They view that time is system of possible positions of possible events related by before, after and simultaneous with. Time in Oriental Poetry and to be more precise, in Sinhala poetry is heavily linked with the Buddhist concept. From the point of Buddhist philosophy, life is infinitely short; we are what we are because of the time it takes one thought or sensation to succeed another life in time is like a dewdrop or a bubble in water. It is this concept what we find repeated in Sinhala poetry.

I believe that I should now briefly introduce what Sinhala poetry is. Its history and development should be recorded in a summary form.

Like in most literatures, in Sinhala literature too poetry preceded prose. Dr. S. Paranavithana refers to four Brahami inscriptions (JRAS. Vol. xxxvi No. 98. 1945) of about the first century BC which are supposed to have been written in verse. One of them is a eulogy of Lord Buddha. Ever since that time numerous references to poetry are found in our annals of history – the Mahavamsa and the Chulavamsa.

During the reign of Kithsirimevan (362 – 390AD) when Lord Buddha’s Tooth Relic

was brought Sri Lanka, it is said that a poem was composed on the history of the adventures of the Tooth Relic.

Though this poem is lost to us its metrical compositions can be identified in a later, which again deals with the history of the Tooth Relic. The chronicle of Chulavamsa speaks Moggallana II (537 – 556AD) as a cleaver poet (CV. Xii-Verse 55). The reign of Aggabodhi I (568 – 601AD) is referred to as a great period of literary activity. Twelve poets seem to have flourished during this period. In fact their names too are mentioned in the Nikaya Sanghrahaya (one of our foremost historical works) as follows:

Sakdamala, Asakdamala, Dami, Babiri

Dalabiso, Anurut, Dalagot, Kumara, Dalasala Kumara, Kithsiri Kumara

Puravadu Kumara, Suryabahu, and Kasubkotapa

From their names it appears that some of them even belonged to the royalty.

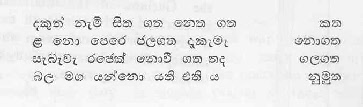

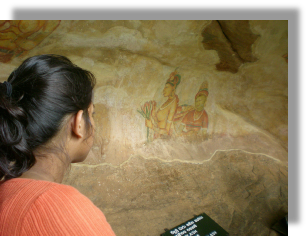

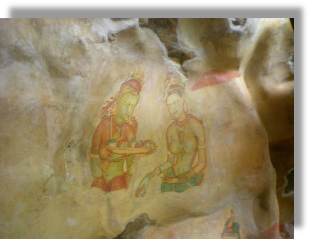

From about the 9th to 11th century we inherited a rich poetical tradition with the Sigiriya Graffiti, which is a clear indication that by this time Sinhala poetry had reached a very high standard. Of the 685 verses deciphered by Dr. S. Paranavithana (Sigiriya Graffiti vol. 1. 11 Oxford University Press – 1956), I give only one example to illustrate this enormously rich poetic tradition. No. 51,

Dakut nami sitha gatha netha gatha katha

La no pere jala gatha dakama nogahta

Sabava rajak novi gatha thada galagatha

Bala maga yanno yathi ethi ya numutha

When (I) saw the lovely woman, my mind inclined itself (to her and she) took (to herself) my eye. If (you), having seen have not accepted me (as your lover) your heart was never a blame in former days. In truth a king has not been accepted (by you; but) a hard rock had been accepted. Wayfarers go and come; look unceasingly (now).

As in Sri Lankan culture and history Sinhala poetry too was influenced by the neighbouring sub-continent India. Sinhala poets took their model from Sanskrit literature. The earlier Sinhala poets were therefore keen followers of the great Sanskrit masters like Kalidasa, Magha etc. the Ornate poetry such as the Muvadevdavata and the Sasadavata for example, follow very closely the Sanskrit Mahakavyas. However the best example of Sinhala Mahakavyas is the Kavisilumina (the Crest Gem Poetry) though follow the Sanskrit model has a creative independence its own.

As when the Sinhala poetry grew through the ages of independent thinking and creative talent seems to have had an effect in no small measure. It is sufficient at this moment only to classify the various categories of poetry extant in Sinhala literature. Firstly we have the ornate poetry or the classics (Mahakavyas) as mentioned earlier. The poets also call this the Gee poetry because of the particular metre used. The four lined verses called the Sivpada Kavya are best exemplified in works like Guttila Kavyaya, and the Kavyasekharaya. The Sandesa poetry or the message poetry is modeled on the famous poem Meghaduta of Kalidasa. This form of poetical composition gives ample opportunity to its author to display his creative talent particularly in descriptions of natural phenomena and the environment. The oldest such Sandesa poem is the Mayura Sandesaya – the Peacock Message. Other best-known examples are the Tissara Sandesaya – the Swan Message, Parevi Sandesaya – the Doves Message, the Selalihini Sandesaya – the Starlings Message, Gira Sandesaya – Parrot Message and the Kokila – the Cuckoos Message.

A third category of Sinhala poetry is the Didactic Verse. Very often the Sinhala poet resorted to giving advice in gnomic sayings. The oldest such didactic poem is the Dahamgeta Malaya – the Garland of the Knots of Doctrine, which can roughly be ascribed to the thirteen century. The Lovadasangarava is a very important such poem which is popular even today. The concept of time is meaningfully expressed in the Lovadasangarava in the following verse.

Anda anda eyi maru pin kara ganne

Kelasada sitha maru neti sithanne

Kumatada ka bi nithi sarasenne

Kothanada me kaya aragena yanne

A literal translation of this verse is as follows;

Acquire merit thinking you will die today

How can you tell that death will not come tomorrow?

Why do you eat and drink and adorn yourself?

Where do you hope to take with you this body of yours?

A cento of such didactic verses is found in a work called Subhasithaya-words well spoken. They are sayings to guide the contemporary life of the Sinhala people. For the example the eternal truth of achieving benevolence through overcoming hatred is given expression in the following verse;

Nopanath aya anatha ahasev natha niyama

Emhatbavin vanasamu noyode savama

Tama sittulehi vera nasuvot no tabama

Vanaset ohu savoma diyavan gini sema

(SUBHASITAYA)

“The lawless are to be found every where, like the measureless sky, and as they are countless all of them cannot be destroyed. If one destroys completely the anger in his mind, all the wicked will be destroyed like fire plunged into water.”

The longest didactic poem in Sinhala is the Lokopakaraya – the help of the world, consisting of two hundred and thirty eight verses, composed in the Ge metre like the earlier mentioned Mahakavyas – Ornate Poems.

Fourthly, we have the Panegyrics and war poems – the Prasasti Kavysa. Sinhala poets from very early times up to-date are patronised by the royalty. The poets too on their part performed their duty in signing praises of those who supported them. In this as in the other categories of poetry, the Sanskrit Panegyrics influenced them.

The earliest such Sinhala Panegyric poem is the Parakumbasiritha, (the history of Parakramabahu). In this poem and in other eulogies the poet has used the metres in the various stages to suit the drum and other instruments to accompany the dancers and the girls who sung these verses. Prasasti Kavysa are very eloquent in using metres to heighten the pitch of emotion through forceful and sonorous words with alliteration.

Of the war poems mention may be made of the Konstantinu Hatana (the war of Constantine) an eulogistic description of war in which General Constantine de Sa Noronha won a battle against Sinhala rebel. Another collection of panegyric verses in praise of Rajasingha II is the Parangihatana - “the war with the Portuguese.” In later Prasasti Works, much prominence has given to the erotic sentiment (Sungararasa). A collection of verses and songs sung by the dancing girls has come down to us in the Srungalankaraya (description of erotic sentiments).

The fifth category of Sinhala poetry is the Eulogies description of the Buddha. These are the poems dealt entirely with the enormous good qualities of Lord Buddha. The best known example is the Budugunalankaraya (ornament of the virtues of the Buddha). The other similar eulogies are Prathiharyasatakaya (the hundred stages on the miracles), Teruwanmala (the garland of the Triple Gem) and the Tunsarana (the refuge of the Triple Gem).

Lastly the Love Poetry occupies a significant place in Sinhala poetry. Apart from the Classical Poems referred to earlier in discussing the Ornate Poetry in later poems like the Viyovagaratnamalaya (the Gem Garland of verses of Separation). We have had a famous poetess called Gajaman Nona to whom many erotic verses are ascribed. One instance where an admirer gives advice to her and her reply to him is as follows;

Yana me gaman apa uni nam paramada

Vena salelun desa nobalan sithu peda

Alapatha pan waki vilasin novahada

Sithata ganin lande mama dun avavada

My girl, though I got late on this journey which I am undertaking

Do not look at other youths with desire in your heart.

Have no attachment anyone. Be immune to others’ advances!

Keep this advice in your mind

Gajaman Nona replies him in the following verse;

Oba yana gamvala anganun novasada

Enu vigasin ehi novamin paramada

Himiyani dan oba mata dun avavada

Mama ivasam madarada ivasum deda

My Lord, are there no women in the villages to which you go?

Do not delay but come back quickly

I shall keep in mind the advice you have given me,

But alas, will Cupid permit me to keep my troth.

Another poem on the subject of sex and passion is the Rataratnalankaraya, ‘the Ornament of the Gem of passion’ which is apparently based on the Kamasutra.

Legend and history too occupies a prominent place in Sinhala poetry. The story of the founder of the Sinhala race is narrated in such works as Kuweniasna etc.

The last phase of Sinhala poetry is popularly known as the “Colombo Period.” The contemporary Sinhala poet is inspired not only from the Indian poetry but also form the poetic tradition of the West. However the contemporary Sinhala poet is very keen to retain the metre, normally the four-lined stanza that gives the facility of recitation. The verse libre or the free verse to has had its influence on the Sinhala poet particularly in expressing subtle contemporary concepts.

To conclude I quote from a speech made by Honourable R. Premadasa, Prime Minister of Sri Lanka, delivered at the 49th Anniversary Celebrations of “Aganuwara Tharuna Kavi Samajaya” on 28th April 1984, at Tower Hall in Sri Lanka.

“Let us receive encouragement from the creation of artists of yesteryear, and cater to the need of the modern world, while organizing programmes of work for the future. To do this through our arts and crafts we should learn of the works of the art of foreign countries and decide to improve our own works of art to suit the needs of the time.

While preserving the arts and crafts of yesteryear as symbols of various eras, and creating arts and crafts to suit the needs of the present, let us endeavour to provide inspiration to future generations. I would like to summaries this idea in just one verse;

‘Tis not in the hand that can pen a mere four lines

That the art of the poet resides, I surely think.

‘Tis in the heart of the one who is good and wise

That such art rests and no where else, I think.”